This article I wrote a year ago featured first on the digital pages of Vox Cricket. Major publications are chained to news cycles and topical stories, and none of them could find the space for this. But this one is close to my heart, so I thought it should be out there.

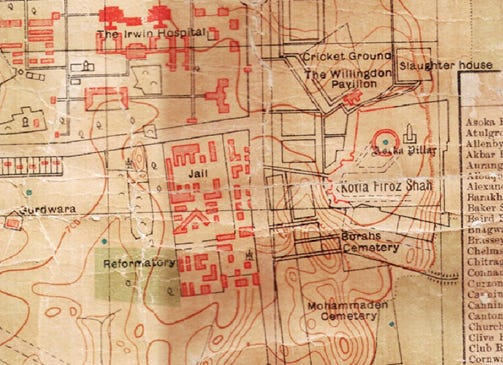

The Revolt of 1857 ended the rule of the Mughal Empire, and the reprisal of the British forces left their capital of Delhi ravaged in its wake. In the decades after, the British, now fully in control, decided to shift their capital to Delhi, which had long been a seat of temporal and spiritual power. They pushed a policy of urbanisation in their imperial capital, and as part of this, commissioned a cricket ground on the outskirts of the old city. Located next to the citadel of Feroz Shah, the 14th century ruler of Delhi who came from the Turkic Tughluq dynasty, this ground now takes his name, the Feroz Shah Kotla.

Despite the royal connections, the Kotla fails to evoke the romance associated with an Eden Gardens or a Chepauk. There are no iconic Pongal Tests held there, no mind-boggling crowd capacities to boast of. Instead, the modern North stand is often derided as a macabre cousin of a car park. Add to this the sorry image of the Delhi District Cricket Association as a hotbed of corruption and incompetence, and Delhi gets relegated to the backseats of the Indian fan’s perception.

***

The Kotla ground’s old Willingdon Pavilion, that sits behind the South Stand, was inaugurated in 1933 by the then Viceroy of India, The Earl of Willingdon. Since then, the ground has been witness to some iconic moments in Indian cricket history.

Independent India’s first Test match at home was played in 1948 in Delhi, on a turf pitch. A strong West Indies team made their highest ever Test total of 631, with Lala Amarnath’s home side holding on to a tense draw.

The same Hemu Adhikari who had held fort to a draw in 1948 combined with Ghulam Ahmed for a record 10th wicket stand of 109 runs in 1952 against Pakistan, giving India an innings win over the archrivals. This was the first Test between the two nations, and was inaugurated by India’s first president, Rajendra Prasad. The Pakistani team was led by Abdul Hafeez Kardar, one of three men to have played for both India and Pakistan.

Perhaps best known for Anil Kumble’s record 10-wicket haul against Pakistan in 1999, the Delhi ground brought the best out of India’s most successful spinner. He took 58 wickets in 7 Tests, averaging a measly 16.8. He also played his final Test match here, his last wicket being a running caught and bowled despite his hand carrying eleven stitches. He was carried off the ground on the shoulders of his teammates to a rousing reception.

The ground has been a happy hunting ground for India’s spinners before Kumble as well. In 1965, S Venkatraghavan’s 12 wickets on a dry surface, helped by tons by Dileep Sardesai and Tiger Pataudi, helped India beat the touring New Zealand team by seven wickets. In the Delhi Test of 1969 versus Australia, Bishan Singh Bedi and Erapalli Prasanna bowled 80 overs for 8 wickets on an “absolutely grassless pitch” (according to Wisden). In the second dig, Pataudi introduced the pair after just three overs from the “new ball bowlers”, and they took 5 scalps each, consigning Australia to a seven wicket loss.

Indian batting too has seen some milestone moments at the Kotla. In 1983, Sunil Gavaskar, the original Little Master, made his 29th Test hundred to overcome Don Bradman’s tally, stroking an attack boasting of Holding and Marshall for 121. 22 years later, Sachin Tendulkar, in many ways his successor as India’s legend from the Mumbai school of batting, overtook Gavaskar’s tally of 34 Test centuries on a hazy day here against Sri Lanka.

Delhi also was home to the relatively unknown coup-de-grace of the man who was called the “Bradman of India”, Vijay Merchant. Merchant returned to Test cricket after a gap of five years, making a sparkling 154 against England in Delhi, at the ripe old age of 40. At that time, this was the highest Test score for an Indian. In the same match, Vijay Hazare, often his competitor for the title of India’s best batsman, bested this with a 160. Merchant injured his shoulder in that match, and never played for India again.

India have been undefeated at the Feroz Shah Kotla ground since 1987, with their most recent victory being a 337-run walloping of South Africa that featured a fourth-innings blockathon for the ages. Hashim Amla and AB de Villiers put on a masterclass in defence, facing a whopping 541 balls for combined scores of 68. Victory was delivered by a fiery Umesh Yadav spell that lit up a grey final day.

***

That the Kotla has been a fortress for India is fitting, as the colloquial name itself means “fort”, taken from the structure bordering it.

Delhi is a city of cities, a landscape dotted with the settlements of successive kings, spread in a triangle between the ancient Aravali hills and the Yamuna river. Ferozabad, built by Feroz Shah Tughluq in 1354, is known as the fifth city of Delhi, which started from the northern ridge near the Delhi University campus, and went unbounded to the south.

The “Kotla” (fort) was its central citadel, and today houses one of two Ashokan pillars in Delhi (the other standing at the northern ridge). Erected in 240 BC, it features inscriptions in both Brahmi and Pali scripts. The structure that houses it sees devotees of the djinns, creatures from Islamic mythology that are said to have inhabited Delhi since medieval times. Every Thursday, the fort sees a procession of fervent followers in their honour. It is their love for the city that keeps the city thriving through the rise and fall of different empires. Devotees spend hours in prayer, pasting letters with their wishes and aspirations, lighting lamps and tying amulets all around.

The complex also has a baoli, a medieval step-well, a network of which ran throughout Delhi, supplying water. The Grand Mosque (Jami Masjid) that stands at the edge the fort was so magnificent that Timur stopped there for prayers in 1398.

The ground and the fort lie just outside the southern boundary of “Old Delhi”, the name given to emperor Shahjahan’s walled city, the seventh and final “old” version of Delhi. It is a world in itself, conserving the way of life of a bygone era. A drive along Delhi’s outer ring road, where the Yamuna used to flow, delivers views of the Red Fort, the Old Fort (the sixth city), and the Kotla, with the pillar tall, and the stadium lights in the background, juxtaposing the new and the old, giving an impression of moving through time while moving through space.

On Bahadur Shah Zafar Marg, where one enters the stadium, there lies the grand Kabuli Darwaza (gate), which served as an entrance to Sher Shah Suri’s city, built after Ferozabad. At the fall of the Mughals in 1857, the last heirs of the dynasty were shot dead and hung here for display for three days. Perhaps that is why it is now called the Khooni (bloody) Darwaza. A little further north is the Delhi Gate, the southern gate of emperor Shahjahan’s city. Sunday mornings used to see a mile-long bazaar of second-hand books, with everything from pulp fiction to niche collectibles available at a fraction of the market price, which was recently moved away.

Visits to the Kotla are never complete without gorging on the authentic Delhi food that neighbours the area. The stadium borders Ansari Road, which skirts the edge of Old Delhi. Before the morning session of a Test, this place offers a quintessential Delhi breakfast of aloo-poori (fried bread with potato curry), sold by migrants who came to Delhi after the Partition of India for more than 40 years. Further inside Old Delhi, one can find nihari, a rich, spicy mutton or buff stew, cooked overnight and served with thick flatbread.

After day-night games, one can go back to Old Delhi to visit the iconic Karim’s, an eatery serving authentic Mughlai food since the Delhi Durbar of 1911. It remains open until late in the night, and remains jam-packed after matches at the nearby Kotla. My fondest memory there was sharing a table with four other groups at 1 am after an IPL game, digging into red-hot chicken curries and kebabs. The frills and fancies of fine-dining are absent, the focus is on the grub.

The Feroz Shah Kotla ground courts history and culture, in more ways than one. It takes its name from a magnificent medieval fort, and borders an imperial walled city, replete with delectable food and unique heritage. And it has seen some of Indian cricket’s greatest moments. The next time you buy tickets to it, remember and explore the remarkable past and present of the place, both on and off the field.

Digital Marketing Trainer